How Pig Ovarian Cyst Affects Sow Fertility Cycle

For many pig farmers, nothing is more frustrating than seeing healthy-looking sows fail to conceive or show irregular heat cycles. When that happens, one of the silent culprits often hiding in the shadows is the ovarian cyst. While it’s not always easy to detect without the right tools, understanding how these cysts develop and disrupt the reproductive rhythm of a sow is crucial for maintaining farm productivity.

What Are Ovarian Cysts in Sows?

An ovarian cyst is basically a fluid-filled sac that forms on the ovary and doesn’t go away like a normal follicle would. In a healthy sow, follicles grow, mature, and either ovulate or regress. But sometimes, due to hormonal imbalances or stress, one or more follicles fail to ovulate and just stick around, becoming cystic. These cysts can interfere with the sow’s normal estrous cycle, and they often go unnoticed until fertility rates start to drop.

Veterinarians typically categorize ovarian cysts into two main types:

-

Follicular cysts: These are the most common. They’re usually thin-walled and secrete estrogen, which may cause prolonged or irregular heat signs.

-

Luteal cysts: These have thicker walls and produce progesterone, often suppressing the heat cycle entirely, making the sow appear anestrus (non-cycling).

How Cysts Affect the Fertility Cycle

In a normal reproductive cycle, hormone levels fluctuate in a precise order. Estrogen rises during follicular development, triggering estrus behavior and, eventually, ovulation. After ovulation, progesterone takes over to support pregnancy. But when a cyst develops, that entire sequence can get thrown off.

If a sow has a follicular cyst, she may show prolonged heat, stand for mating multiple days in a row, or even return to heat irregularly. Farmers may mistakenly breed her at the wrong time, resulting in failed conception.

With luteal cysts, on the other hand, the sow may not come into heat at all. These sows are often labeled as “silent” or “non-cycling,” which can be misleading because their ovaries are active—just in the wrong way.

Common Signs and What to Watch For

Spotting ovarian cysts isn’t always straightforward, especially without imaging tools like ultrasound. But a few signs can tip farmers off that something might be wrong:

-

Irregular or prolonged estrus behavior

-

Sows not returning to heat after weaning

-

Repeated mating without conception

-

Low farrowing rates in certain age groups

-

Extended weaning-to-estrus intervals

Sometimes, sows with cysts still show heat signs, but breeding them doesn’t lead to pregnancy. That’s when it’s worth digging deeper.

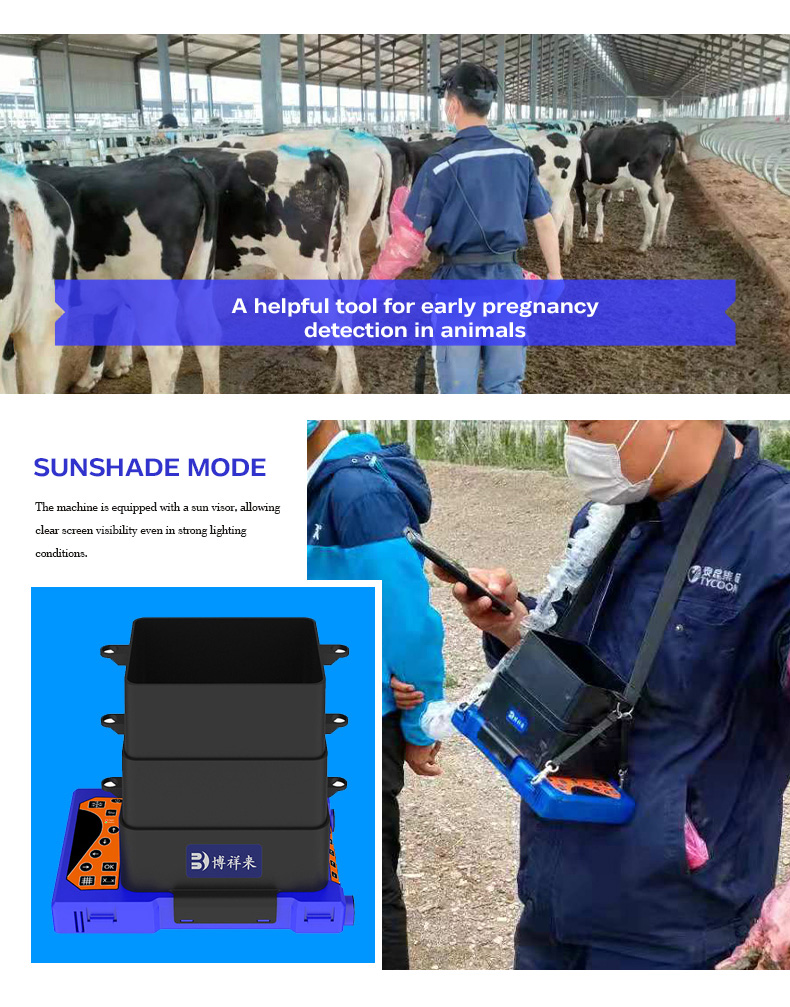

How Ultrasound Helps Detect Cysts

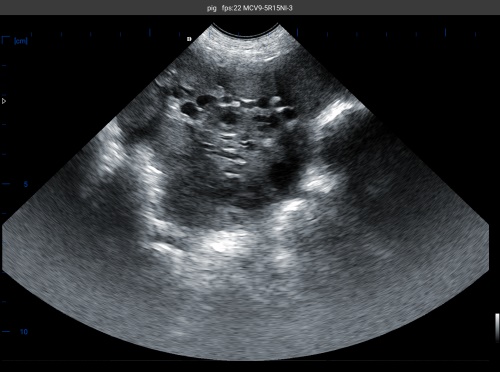

Veterinary ultrasound, especially transabdominal or transrectal probes, has become a valuable tool in modern swine herds. It’s non-invasive and gives a real-time image of the ovaries and uterus. With some practice, it becomes fairly easy to distinguish a normal follicle from a cyst.

Follicular cysts appear as large, round, thin-walled fluid structures, while luteal cysts tend to have thicker walls and less clear borders. Ultrasound allows for early detection and appropriate treatment before reproductive performance is seriously affected.

Many farms today schedule routine reproductive scans on sows showing abnormal cycles. These checks save time, avoid unnecessary breedings, and help target veterinary treatments more accurately.

What Causes Cysts to Develop?

There isn’t one single cause, but rather a combination of factors that can disrupt the hormonal environment in the sow:

-

Stress: This could be from heat, transport, weaning, or even mixing with other animals.

-

Poor body condition: Underfed or over-conditioned sows are more prone to hormonal imbalances.

-

Endocrine disruption: Irregularities in the release of LH (luteinizing hormone) can prevent proper ovulation.

-

Inadequate boar stimulation: In younger gilts, insufficient exposure to mature boars can delay or disrupt normal cycling.

-

Genetic predisposition: Some lines may be more prone to reproductive issues, especially under poor management.

Management Strategies on the Farm

Dealing with ovarian cysts requires a multi-angle approach. Simply treating one sow won’t solve the issue if the root causes aren’t addressed.

1. Regular Heat Monitoring

Accurate recording of heat signs post-weaning is key. If a sow fails to come into estrus within 7 days, she should be checked.

2. Ultrasound Scanning

Bringing in a vet for ultrasound once a month can help catch issues early. It’s especially useful for sows that have had multiple breeding failures.

3. Hormonal Treatments

Depending on the cyst type, vets may recommend GnRH (gonadotropin-releasing hormone) injections to stimulate ovulation or PGF2α to regress luteal tissue. But these should only be used after a proper diagnosis.

4. Nutrition and Body Condition Scoring

Ensuring sows have optimal body condition—neither too thin nor overly fat—supports hormonal balance and reduces risk.

5. Reduce Environmental Stress

Consistent handling, ventilation, and temperature control all help to maintain sow welfare, which has a direct effect on reproductive performance.

Real-World Observations from Farms Abroad

On European pig farms, reproductive efficiency is closely tracked with performance software. When non-productive sow days (NPDs) go up, cysts are often part of the investigation. Scandinavian farms, for example, use ultrasound routinely to keep track of ovarian structures, and they’ve found that early weaning stress increases the rate of cystic follicles by 15–20%.

In North America, especially in commercial operations with over 500 sows, the approach is more tech-driven. Farms often combine heat monitoring apps, feeding data, and vet ultrasound scans to build a full reproductive profile of each sow. This holistic monitoring catches subtle changes early—sometimes before any outward signs appear.

The Bigger Picture: Impact on Productivity

One sow with a cyst may not seem like a big issue. But when 10–15% of a herd starts showing irregular cycles or reduced conception rates, the economic impact snowballs. More empty days, higher feed costs, and fewer piglets per sow per year all add up.

Moreover, repeated breeding attempts on cystic sows can increase boar workload and reduce semen efficiency. So, catching and correcting the problem early can improve both animal welfare and farm profitability.

Final Thoughts

Ovarian cysts in sows are a hidden challenge many pig farmers face without realizing it. They quietly interfere with the normal reproductive rhythm, leading to missed heats, poor conception, and wasted resources. But with better understanding, modern tools like ultrasound, and a sharp eye on sow behavior, it’s possible to manage—and even prevent—most of these cases.

Whether you run a small family operation or a large commercial farm, keeping a close watch on your sows’ reproductive health should be part of the weekly routine. The payoff is a more efficient herd, better planning, and stronger financial returns.